Following my annual tradition, this is a round up of some of the best books I read in 2024. For previous roundups, see 2014, 2015, 2016, 2017, 2018, 2019, 2020, 2021, 2022 and 2023.

What a year. A huge amount of my energy this year went into attempting to understand the German position on Palestine and Israel – a position which fundamentally makes no sense to me, one which takes convoluted German guilt for the Holocaust, mixes it with a heavy dose of Islamophobia and racism to produce absurd positions like rewriting history to accuse immigrants of ‘importing’ anti-semitism to Germany – and ends up with both condoning and supporting a genocide. I’ve been in Germany now for 13 years, and I’ve never felt such utter confusion and alienation in the city I chose to call home, one which I thought (wrongly) I mostly understood and felt at home in.

It’s not that this is the first time I’ve seen people dehumanise other groups, of course, but this is the first time I’ve seen people who previously stood for ‘human rights’ or ‘social justice’ or who see themselves on the political left, go through such baffling mental gymnastics to avoid having to rethink or reexamine their education and socialisation with regards to Palestine. It’s been alienating, it’s been painful, and frankly it’s been exhausting to have to sit there and defend the basic humanity of Palestinians, Muslims, brown people, over and over again.

All that to say: my book-reading this year took a back seat, while I searched for sources of information that would help me at least try to understand what was going on in German society. I devoured podcasts and longreads and sat down with German friends to ask them again and again, how, how, how could this be happening. And for most of the year, it all left me with little appetite for delving into a fantasy world or losing myself in a good book.

On this topic, the podcast that I found the most helpful by far, was this very long one from the Dig, featuring journalist Emily Dische-Becker – her deep, factual knowledge on German history and how Germany ended up here, was truly astounding. I can only recommend it. If you’ve not been following the wild anti-Palestinian repression in Germany over the last year or so, this article is a good summary – though it’s from almost a year ago, and be assured, things have gotten much worse since then.

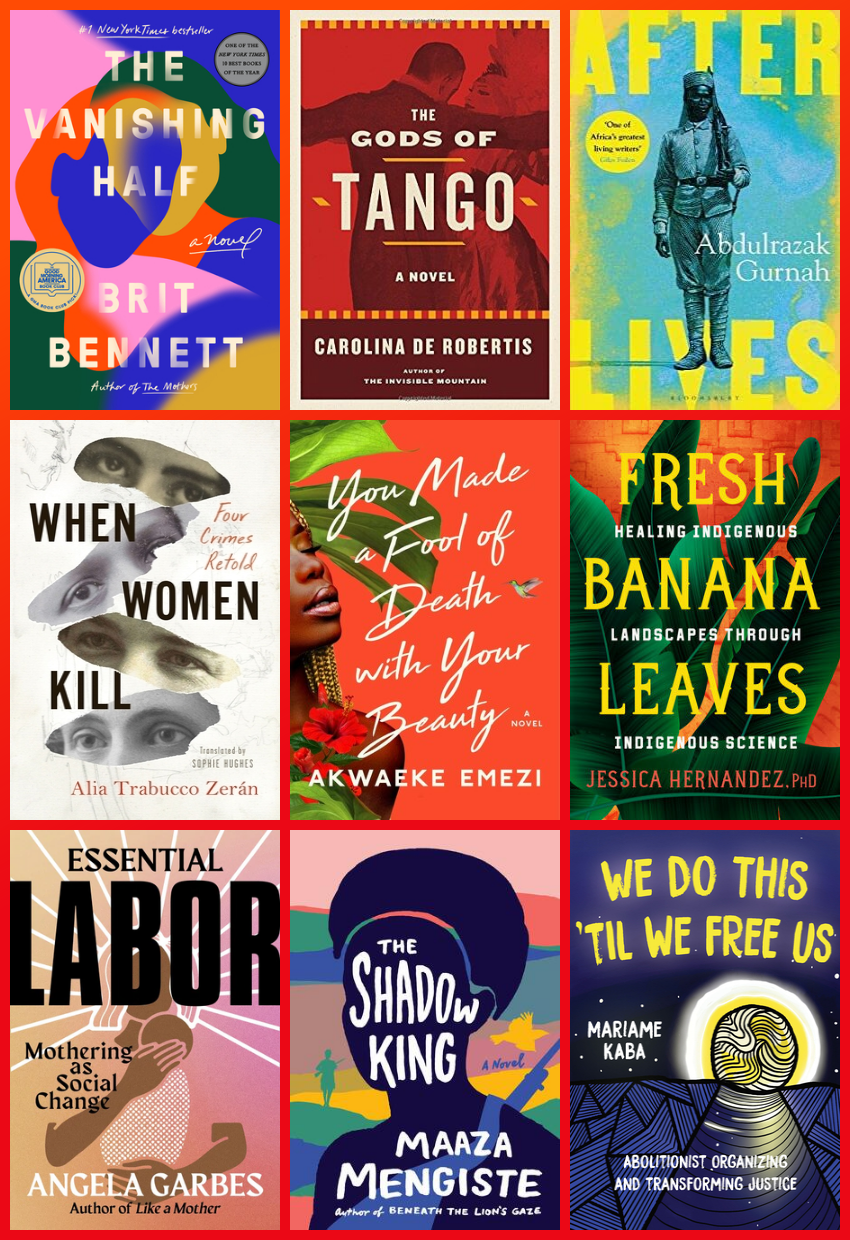

But to the books that I did manage to read: 26 in total, primarily fiction. It was #ReadPalestineWeek at the end of November, which gave me motivation to read some more Palestinian authors; and I continued with my subscriptions to Tilted Axis Press, and the absolutely wonderful Hajar Press, an independent and “proudly political publishing house run by and for people of colour” in the UK. Every single one of the Hajar Press books that I’ve received have been like nothing I’ve read before, with truly transformative ways of thinking. If you’re in the UK, I really recommend their subscriptions – it’s such a joy to get their books in the post every few months!

Stats (or not)

I’m reluctant, this year, to reduce the authors of the books I read to their visible identities. I know, I know – I’ve done it for years! But the limitations of that approach are also extremely clear to me (see: my own book about how categories are reductive and unhelpful!) It’s also extremely obvious to me how, for example, people of colour can have deeply rooted internal racism that make what they have to say absolutely not what I want to be listening to. (UK politics provides some stellar examples: Suella Braverman, Rishi Sunak, and others). As I learn more about abolitionist thought, transformative justice, and more – I’m more interested in making sure that the sources of information I’m learning from are pushing towards shifting power, examining social structures that we take for granted, shining a light on oppression and describing what futures we want to be building towards, creating new myths of who we are and how we relate to each other, and more.

So for this year, I’ll say: the vast majority of books I read fell into that category.

Favourites

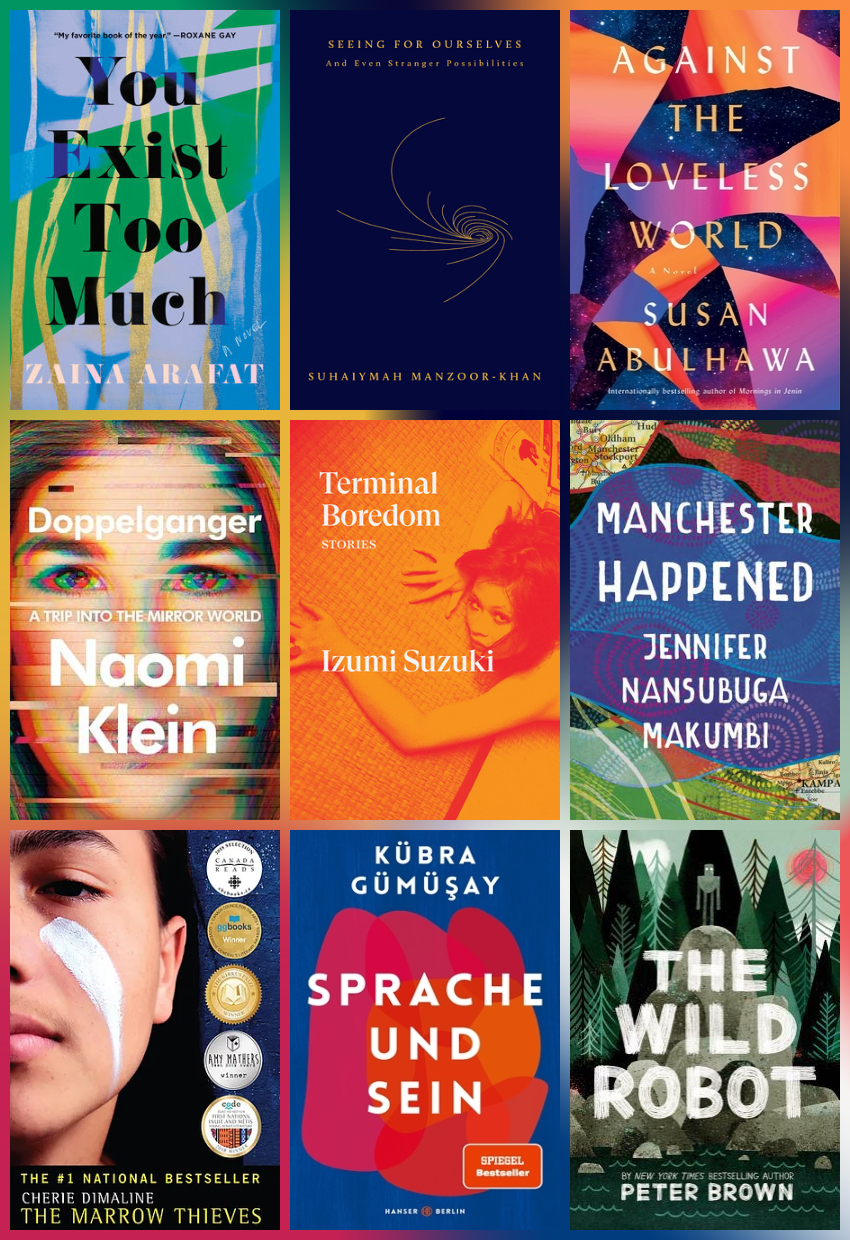

If you’re going to read one book from this list, make it this: Against the Loveless World, by Susan Abulhawa. A necessary gut punch of a book that I picked up during Read Palestine Week, I just couldn’t put this down once I’d started. So much of the mainstream discussion around Palestine in the last two years has completely failed to take into account the decades of injustice prior to that, and this provides a gripping, at times brutal, story of one woman’s life under Israeli occupation.

Best short story collection Terminal Boredom, by Izumi Suzuki with Aiko Masubuchi (Translator), Helen O’Horan (Translator), Daniel Joseph (Translator), Polly Barton (Translator), Sam Bett (Translator), David Boyd (Translator). This was the first time I read anything by Izumi Suzuki, a Japanese writer and actor who died in 1986 at the age of 36, and who wrote some incredible feminist science fiction novels and stories and novels, many of which are gathered in this collection. If you’re into Ursula K. Le Guin (you know I am) you’ll love these.

A close second best short story collection Manchester Happened, by Jennifer Nansubuga Makumbi – a collection of short stories set between Manchester, UK and Kampala – these stories all bring into question the idealised and desirable ‘West’, the deep sacrifices immigrants make, and all with a heavy dose of compassion. (Also, Makumbi’s other books – Kintu, and The First Woman, were previous favourites of mine from past years.)

Best non-fiction: Seeing for Ourselves: And Even Stranger Possibilities, by Suhaiymah Manzoor-Khan. This book, by Hajar Press, was just fantastic, combining Islamic teachings with transformative justice principles. “On seeing and being seen”, it’s a book that I wrote down so many quotes from and will be thinking about for a long time.

Best young adult: The Marrow Thieves, by Cherie Dimaline – I was sent this book through a kind of instagram-faciliated chain-mail book giveaway thing, whereby I sent one person a book and received maybe 5 or 6 books in return from people I didn’t know, and I’m so glad I took part! This was a book I probably wouldn’t have come across – indigenous science fiction, dystopian, with strong ideals and a gripping story.

Special mentions

Kids’ chapter books My son started getting into chapter books, which is a very (very!) exciting development for this bookworm of a parent. I was thrilled to discover that Ursula K. Le Guin wrote a couple of children’s books, and we started with Catwings which was not quite what I was expecting, and too short for my liking, but good. But the one I loved most was The Wild Robot by Peter Brown which was just a lovely, well-written and child-appropriate book with some lovely themes. I’m excited to read the others in the series (and to watch the film!) Recommendations for chapter books, very welcome!

Tech-related non fiction I don’t read much in this category these days, but seeing all the buzz around Naomi Klein’s Doppelganger, I felt like I had to. And it was indeed really good, though perhaps not quite as aware of her own privilege and position as I might have imagined. It’s a good mix of personal narrative with solid reporting, and a necessary take on current politics and tech and how we relate to digital ‘versions’ of ourselves.

Non fiction Sprache und Sein, by Kübra Gümüşay – I’ve followed and loved Kübra’s work for years, and had the absolute pleasure of seeing her give the opening talk at the Muslim Futures exhibition, which gave me the motivation to pick up her book. As a linguist and a feminist, I feel like I’m right at the intersection of the target audience for this book which explores how we can have more understanding and compassion for each other within (or despite) our words. (Also available in English - Speaking and Being: How Language Binds and Frees Us)

Fiction You Exist Too Much, by Zaina Arafat – another as part of Read Palestine week, this time a queer tale of immigration, love, belonging, and balancing different identities.

Fiction Yellowface, by Rebecca F. Kuang Ahh, what a brutal take down of the publishing industry and more. This was so good, one of those ‘can’t put you down’ books that was easy to read and also so (slightly darkly) funny at time.

YA Fiction Bitter, by Akwaeke Emezi I love Emezi’s writing, and this was such a captivating story. I’ve read it at least twice now, and have probably recommended it here before – but it’s a great, imaginative, thoughtful, reflective take on revolution and making change (and being brave).

For the full list of books I read, see my Storygraph profile here.