Following my annual tradition, this is a round up of the best books I read in 2025. For previous roundups, see 2014, 2015, 2016, 2017, 2018, 2019, 2020, 2021, 2022, 2023, 2024.

This year, my reading was mostly shaped by the fact that I shifted parenthood seasons – from having a baby and a young child, to having two young and (slowly!) increasingly independent children. It’s still intense, of course, but it’s a different kind of intense, and it’s meant that I was in a place where I felt comfortable doing trips by myself. After five years, this gave me total autonomy over my time for a few precious days, a few times this year. Unsurprisingly, those days coincided pretty exactly with periods of intense reading - what a gift!

Looking through my books at the end of the year, I realise I read a lot of really good books! And it was mostly by accident, as I didn’t have much time for discovering books. Books friends recommended, books sent to me in the post thanks to a subscription to the ever-wonderful Hajar Press and books I read for work made up the bulk of my reading this year.

Also, a massive shout out and love note to Libby, a free app that a lot of libraries across Europe and the US use - after years of refusing to read on anything but paper or my Kindle, I really got over it this year (perhaps also due to many, many hours sitting in a dark room trying to get children to bed, with nothing but my phone for company) and I ended up reading a lot on Libby. I got hold of library cards from friends in different countries and cities, which means I have 5 digital libraries at my fingertips. If you’re able to get over the fundamentally false premise of ‘1 digital copy available, 5 people waiting’ when you have to put an ebook on hold (!)- I can highly recommend it for ease of use and access.

All in all: this year, I read 46 books, a significant increase from the last couple of years. (See above: babies took all my time!) Like last year, I’m not going to reduce authors identities to statistics. But almost of the books I read brought perspectives that were new to me, and amplified stories that I don’t feel like I hear enough - be that via translation, books that were situated in places or cultures I don’t know about, or books that were amplifying histories or perspectives that are structurally marginalised. For next year, I’m keen to read more books that decentre Western perspectives, mostly because I feel like I’ve read a lot of books with some kind of geographic home in the US or Western Europe, and there is undoubtedly a lot more out there.

The author I read the most of

R. F. Kuang. I’d only previously read Yellowface, and this year I read through her whole back catalogue in advance of talking with her at the ILB in September - six books, which felt like a lot given that she’s only 30 years old. My absolute favourite, and one that I’ve recommended again and again since reading it, is Babel. I’m a languages nerd with a soft spot for anti-colonial resistance and fantasy, and this book hit squarely in that intersection. The book explores “translation as a tool of empire” and though it’s not subtle in its messaging, I still loved it. It’s a fantasy novel set in a world where magic is brought to life through the work of translation, specifically, finding word-pairs in different languages that have slightly different but related meanings.

At the International Literature Festival in Berlin this year, I got to talk with her (at a sold out main stage, no less!) about her latest book, Katabasis, which was such a joy. It was also my tenth year of moderating at the festival, which was a lovely milestone to hit! I love talking with authors who manage to make book talks seem like a fun part of their job as an author - she was full of funny anecdotes, and open and friendly to chat with. If you’re new to her repertoire, my favourites in order are: Babel, Yellowface, The Poppy War Trilogy, Katabasis.

Fiction favourites

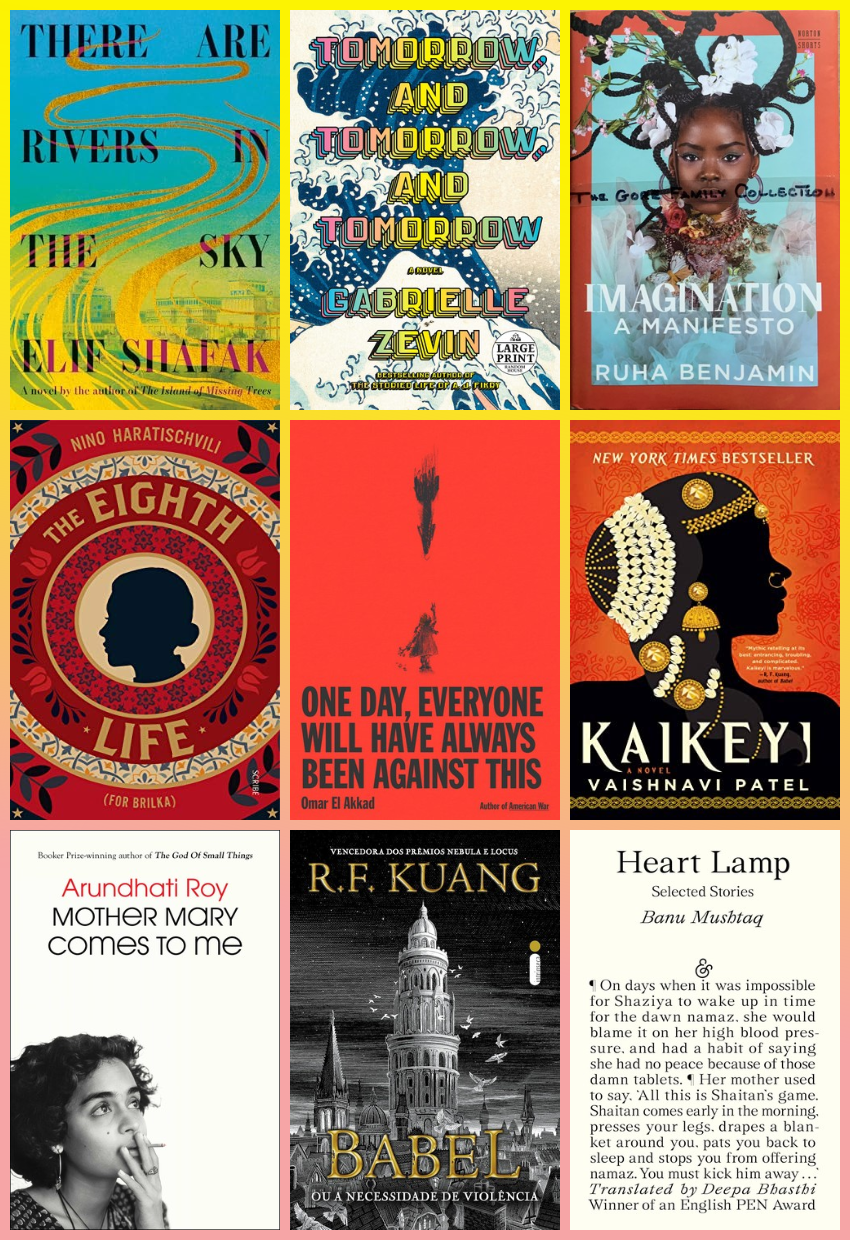

This year it feels hard to narrow this list down, so here’s the shortest short-list I can manage. My fiction favourites from 2025, in no particular order:

Tomorrow, and tomorrow, and tomorrow by Gabrielle Zevin

I started reading this on the recommendation of a friend (thanks Anita!) and had zero expectations. It was adorable, especially if you’re at all into computer games, but also if you’re not. It’s one of those ‘pick this up and forget about everything else in the world’ books, a super absorbing and enchanting and (at times) devastating beautiful book. I’m a bit envious of people who get to read this for the first time.

There are Rivers in the Sky by Elif Shafak

I remain in total awe of the imagination and scope of Elif Shafak’s work. How does one person have so many stories inside them? I’m slowly but surely working my way through her impressive back catalogue, and this was my favourite of hers that I picked up this year. Shafak’s books often jump between different places and times (I’m a sucker for those kinds of books) and this is no different, but the characters across time have a single drop of water that brings them all together. The book goes so deep into different historical periods with such a level of detail - I can’t imagine how much research went into this book.

Kaikeyi, by Vaishnavi Patel

I’d be curious to know how people who are deeply familiar with the Ramayana, an Indian epic poem, will feel about this book - but for me, a newbie to both the tale of Kaikeyi and the Ramayana, it was a fantastic read. It’s a retelling from the perspective of Kaikeyi, a character who is portrayed as a villain in the original. The book is full of complexity and has some really lovely and clever literary devices in it.

Babel, by R. F. Kuang

See above for why!

Heart Lamp by Banu Mushtaq, translated by Deepa Bhasthi

What a wonderful, wonderful book, full of stories that are somehow both unique and somewhat universal. You know that feeling when you read a book or a short story and think, oh, that was kind of similar to that other book, in plot or setting or character? I didn’t get that feeling, not once, at all, with any of these stories. I can almost guarantee that most people reading this won’t have come across similar stories.

I love books that centre non-Western perspectives (similarly: The World Was In Our Hands, below, also does this wonderfully), and reading about how intentionally that was done through the translation in the translators notes was also really fascinating. The book was originally written in Kannada - a major world language spoken by approximately 65 million people, yet, as noted in the translator’s notes: “its presence online is something of a wilderness when compared to Urdu and Arabic.”

I was also thrilled to see that this book was published by And Other Stories - a Sheffield-based independent publishing house where I had a subscription for many years, who publish many fantastic contemporary books.

The Eighth Life, by Nino Haratischvili, translated by Ruth Martin & Charlotte Collins

I know, I’m late to this party - after receiving three copies of this in two languages, I finally conceded and read it. It’s also extraordinarily long. And who knew (I know, everyone already did!), it’s really, really good. It’s both very complex and really engrossing. I perhaps wouldn’t pick this up if I only had a limited amount of time to read it, because I can imagine reading it over a longer stretch of time would make things quite confusing - but if you’re looking for a long read to sink your teeth into (for example, over a holiday!) this is the one for you. I love books that give me an insight into a culture or time period I’m not so familiar with, and this did both.

Who Wants To Live Forever, by Hanna Thomas Uose

I devoured this book! It was fantastic. It also slightly touches on some of the moral issues around emerging technology that I dabble in in my day job - but mixes it with love and longing and life.

Special mentions for people who work in similar fields to me: The Future by Naomi Alderman, and Allow Me to Introduce Myself by Onyi Nwabineli, both felt like they were really good (fictional) takes on some of the tricky moral and policy issues in the field right now. (Social media, children, parents sharing content, for Allow Me; and Big Tech monopolies, for The Future.) Both also very readable and enjoyable.

And one other special mention, for being great and just gloriously absurd: The Saint of Bright Doors, by Vajra Chandrasekera.

Non-fiction favourites

Try as I might, I also can’t reduce this list further. I loved these books, and have recommended each of them so many times since finishing them.

How to fall in love with the future, by Rob Hopkins

I’ve been thinking about this book, or rather, the framing around it, since I read it - the basic premise (my interpretation) being that in order to encourage people to feel agency over their future, we need to cultivate their feeling of longing for a future that they actually want to live in. It goes beyond simple optimism - ‘a better future is possible’ and delves into the importance of longing, of creating visions that people see themselves in and that they are motivated to work towards. In 2025 my work at SUPERRR Lab touched a lot on future visions, and nothing explained the importance of that work better than this book. (There’s also a really wonderful, now discontinued, podcast by the author called ‘From What If To What Next’ which is along very similar themes.)

Imagination, a Manifesto, by Ruha Benjamin

Like, I think, a lot of people working in a similar space to me - I read and loved this book. It’s along similar lines to How to Fall in Love with the Future, in that it explores different visions and imaginations for what our future could look like, and mentions the work of many people who are doing this kind of imagination work.

Mother Mary Comes to Me, by Arundhati Roy

Oof, what a read. I found this quite brutal at parts, and also deeply moving - Arundhati Roy (whose novels I love) writes about her relationship with her mother, Mary Roy, a well-known and successful activist and educator in India who was also incredibly cruel to her daughter. I’m left astonished at how Arundhati Roy writes about their relationship with such empathy and love, without a drop of resentment at the harsh treatment. I saw her speak in person at a conference in Kathmandu in December, and was dying to ask her exactly this question - to my disappointment, she didn’t take any questions.

One Day, Everyone will Have Always Been Against This, by Omar El Akkad

This book filled me with anger and brought me to tears, and feels like one of those books that I deeply wish all journalists in Europe and the US would read. I suspect, though, that specific target audience probably won’t. The double standards are laid out in enraging clarity, and the title says it all, really.

The World Was In Our Hands, by Chitra Nagarajan

I’m a little biased, because Chitra is a dear friend - but this book is like nothing I’ve read before. It’s a collection of first hand accounts she heard, transcribed and gently edited to be in the book, and to do so she held more than 700 interviews over a period of ten years (!). The book brings to life a huge range of perspectives of people living through the Boko Haram conflict, in ways that are both illuminating and a bit unsettling, in the best way.

The book brings much needed complexity to an often over-simplified conflict, and shines a light on the stories that often get ignored because they don’t fit in with the mainstream narratives. Best of all, it’s explicitly written for people who are familiar with the region. This means she makes the choice not to over-explain, but rather to assume, as many people do when writing books in the United States for a “global” audience, that readers will of course know where, for example, Brooklyn is and have a cultural reference for it that doesn’t require explanation. I really appreciated this explicit choice to decentre Western knowledge. (Related, this year I created her Wikipedia page!)

The Patriarchs, by Angela Saini

I love Angela Saini’s books. They’re such an inspiration to me in the way that she combines personal narrative with deep knowledge and research. The core premise of this book: contrary to popular belief of the patriarchy just “being” because it’s the “natural” way for humans to organise ourselves, systems of patriarchy were only created and maintained thanks to active and intentional destruction of other social structures, structures which served people very well (until they were destroyed by people wanting to push patriarchy.) The book goes deep and broad, throughout history and in many geographies, to prove her point.

Special mentions: Through an Addict’s Looking-Glass, by Waithera Sebatindira.