And there you have a sentence that, incredulously, I keep hearing from my peers. At first, I was outraged; mostly, the people saying things like this are women, in their mid-twenties, young professionals working their way up the career ladder, over-achievers, well-educated, independent women.

What do they mean, they're “not feminists” - of course they are! If I asked them who was more intelligent between them and a male colleague, they wouldn't automatically default to the man. They're competitive and ambitious people; there's no crisis of confidence going on there, they know that they're just as capable as the men they work with.

But somehow, they don't consider themselves to be feminists. Perhaps, yes, the word feminism has been hijacked in popular culture to mean something other than 'people who believe in gender equality' – but the thing that shocked me most was that actually, they know that, and when they say they're not feminists, they mean it.

Yes, a woman can be just as intelligent as a man. But of course, believing simply that doesn't make you a feminist. The penny dropped for me while a friend was describing another friend's new boyfriend.

“He really looks after her, and he fixes everything around the house. It's just what she needs in a boyfriend.”

The next clue came soon after.

“My boyfriend would never let me do that!”

And then :

“Of course he doesn't do the cooking, he's the man!”

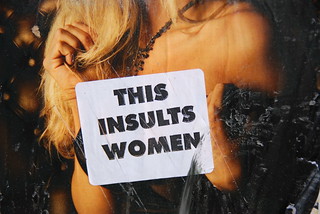

There were more. She, as an independent and well-educated woman, was and is perpetuating a bucket load of gender stereotypes that feminists all over the world have been focused on quashing. And sadly, she's not the only one. Somehow, these misconceptions have been so wired into some of my peers that they are firmly rooted in their cultural and social values.

And, strangely enough, it's apparently entirely possible to be against sexism (sometimes), without being a feminist. Selecting between when you're being discriminated against (sexism=bad) and when you, yourself, are perpetuating the gender stereotypes in a non-offensive way, seems like a funny distinction to make.

Feminism is apparently seen by many as a pipe dream, if that. An unwanted pipe dream might be a better way to describe it. The easy route (as seen by many) : all you've ever wanted is a husband and a house to clean, to have babies, to be looked after and provided for, and yet, for some reason, here these feminists kicking up a fuss when actually, that picture sounds perfect.

The fact that wanting to bow down to these patriarchal structures is seen as 'normal', while wanting to have the same opportunities in life as men is the odd option to choose, baffles me. It baffles me more that women who have truly benefited from the feminists of past generations fighting for that equality now seem so willing to forfeit those rights.

And how do you argue with someone who knows exactly what choices she is making and the consequences of what she is saying? She knows that perhaps more progressive ones amongst her friends will be shocked at her anti-feminist views, but she doesn't care. She's been exposed to all these views, and yet chooses to play the role of housewife. Do we simply accept these views and move on, hoping fervently that those misconceptions that she, as a woman, is 'supposed' to be in the kitchen, is 'supposed' to stay at home and pass up her career, won't get passed on much further?

Somehow, it feels incredibly ungrateful to all the great feminists who have fought for our equality (not to mention the fact that we're not even there yet in terms of equality). Responding to the opportunities that we've been given with resounding denial that we even needed any of them, just doesn't seem right.