I recently started learning how to code, and increasingly, I've been noticing the similarities and differences in the skills I'm developing now and those I developed at university, while studying languages.

“I'm not coding, I'm just copying and pasting” is the answer that came up when someone asked me how good my technical skills were last week. At the time I believed it, too: I was simply looking for what I wanted to make, finding the code behind it, and copying it and pasting it into the appropriate place. I wasn't creating anything new myself, but rather using the building blocks that others had already created.

But isn't that exactly what happens with spoken languages? With first language acquisition, children learn by repetition; they hear things being said around them, and repeat them. In a way, this is the oral version of 'copying and pasting'; and when children do this, we consider it to be 'speaking.'

One aspect I found difficult when starting my foray into coding was (and, this might sound incredibly obvious to those of you who can code!) not being able to recognise what language it was purely from looking at my screen. To me, it all looked the same; black screen, coloured text, incomprehensible words and symbols. Without checking what file I was in from the name or the file type, I didn't know what I was looking at, and of course the rules and the language used differs dependent upon this. I've often tried to insert a line I've seen elsewhere into a file type that doesn't recognise that language, before realising I'm 'speaking' the wrong one. This mistake reminds me of my 3 year old niece and nephew who are learning both French and English and sometimes mix up the languages within the same sentence or phrase.

It's interesting to me that the mistakes I'm making in learning to code are largely similar to first language (L1) acquisition (what babies/children do) as opposed to second language (L2) acquisition as an adult. With L2 acquisition, the mistakes can often come from, for example, falling back on L1 rules to supplement missing knowledge in the new, second language. With coding, this (for me!) is not possible. It makes sense, though, as I am learning my first coding language – although in linguistics, we learn that due to varying social, cultural and physiological developments between children and adults, the mistakes you make as a child will not be replicated as an adult. Me learning how to code seems to be proving this wrong!

Recognising patterns amongst what you're seeing, or hearing, is another common thread; realising that you can break them up into smaller blocks to perform another function is incredibly liberating, on both the coding and the speaking front. Anyone who studied spoken languages at school or university will undoubtedly remember being given a list of set phrases to use in essays, and inevitably these phrases, originally learned by rote, were broken up and used in different ways when it came to exams. So, when I was shown this Global CSS settings list for Bootstrap, it felt wonderfully familiar as the coding equivalent of this list of set phrases.

While there are other similarities between the various learning techniques, there are also some key differences. I've learned spoken languages in a variety of ways; intensive 8 hours a week of grammar for 2 years (bringing me to a basic level of Arabic); French, in small chunks since the age of 11, in France and at university; Spanish, intensively throughout 3 years and a stint in Spain, and German, exclusively by speaking and listening. The outputs of these methods have been varying in terms of the skills they've given me, but in all cases I've happily ended up with the desired skills, through what I believe to be the quickest route there.

Because of this experience, the main piece of advice I give to people wanting to learn languages is to first understand your motivation, and then choose your learning technique from there.

For example, wanting to speak German and be able to take part in conversations, but not being concerned about having good grammar, meant that speaking and listening to people and podcasts was a good technique, while wanting to learn how to read and write formal Arabic lent itself to intensive grammar lessons. So, what are my motivations with learning how to code?

I want to understand the world better.

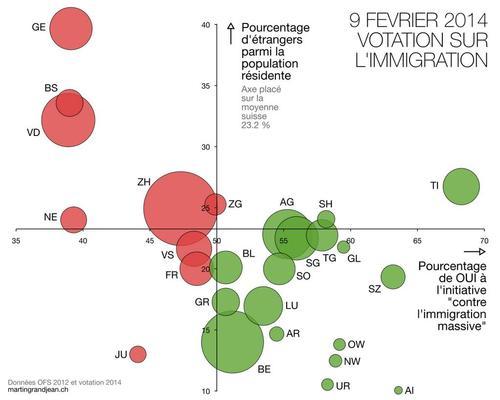

I know that I don't yet fully understand what is possible with programming, and I see on a daily basis exciting projects and examples of programming being used to create things that astonish me. I love the idea of being able to communicate complex ideas to people in a way that they can really easily understand, or being able to help people who haven't (yet) been able to get their voices heard by decision-makers to have a say in how their world works.

So, my motivations in learning to code are complicated, and mixed, and, actually, fairly political. Clearly, this is where my stellar advice falls flat on its face; there's no learning technique here that will help me reach my goal quicker than any other.

There is a key difference between learning a programming language, and learning a spoken language. A desire for communication seems to be the major driving force in learning any language. Whether you want to be on the receiving end of new types of communication (read books in a different language, or watch films), or whether you want to share your knowledge with others (speaking to new people, or writing for a new audience).

The crucial difference here though, is that with spoken languages, you can only communicate with someone who also knows that language. With programming languages, you can communicate with anybody. They can interact with the product of your coding without needing any understanding of how it was made; even if offline or away from a traditional computer, you can create or build things that can change people's perceptions and understandings of the world.

And this is what I find wonderful, and beautiful, and slightly mystical, about coding.