Algorithms. We’re all talking about them, but how many of us actually understand what they are? Tech critics, researchers and academics are sounding warning bells that an increasing societal dependence upon algorithms is potentially very dangerous. Data scientists that I follow, though, are excited by the possibilities that algorithms hold for society. These conflicting views can be confusing - so let’s go back to basics, and consider what exactly we mean when we talk about algorithms.

Let’s start with definitions. Sometimes, I’ve found, writers and researchers talk about algorithms as though they are inherently complex beasts; things that define and govern big data, and help computers run, and nothing simpler than that. A friend suggested to me, though, that replacing the word “algorithm” with “process” might simplify things, and also help flag when people are using the term incorrectly. By definition, there is not necessarily complexity in an algorithm - it’s simply “a set of rules that precisely defines a sequence of operations”, and though we use it largely for computers, it could be anything from describing the set of habits you do in the morning when you wake up, to a recipe that you meticulously and regularly follow.

Thinking about algorithms as a set of decisions - however many millions of decisions there might be in a certain algorithm - makes it a little more human to comprehend, and I’ve found a few different methods of helping me internalise this information. One was reading this blog post on the real 10 algorithms that dominate our world.

In this post, the author, Marcos Otero, describes three vital characteristics needed for an algorithm to be considered valid.

1. It should be finite: If your algorithm never ends trying to solve the problem it was designed to solve then it is useless

2. It should have well defined instructions: Each step of the algorithm has to be precisely defined; the instructions should be unambiguously specified for each case.

3. It should be effective: The algorithm should solve the problem it was designed to solve. And it should be possible to demonstrate that the algorithm converges with just a paper and pencil.

The set of algorithms he goes on to explain also make a lot of sense. They are finite processes, which perform a certain function, and are effective in what they do - just like the characteristics above. He outlines various “building block” type algorithms - ones that form part of an incredible number of processes and systems that happen today, which we are dependent upon.

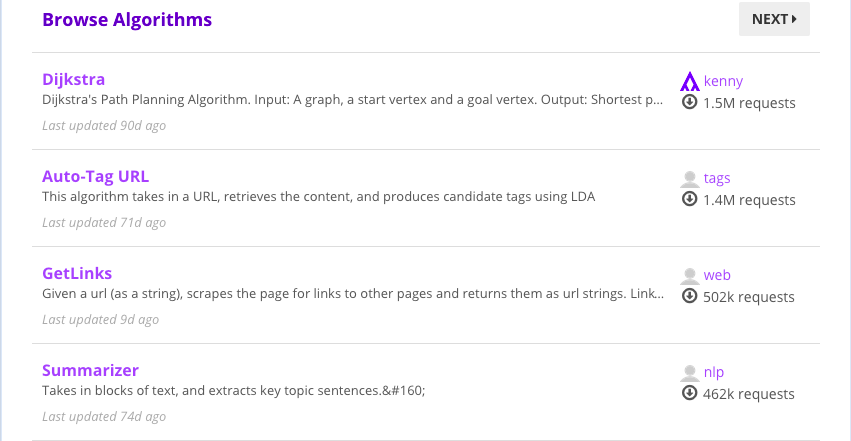

Getting comprehensible explanations is great - but it also always helps to see things with your own eyes. This is where I found Algorithmia to be very useful. Algorithmia is, in their words, an “open marketplace for algorithms”. Users can share algorithms that they create, and anyone can try running algorithms that appear in the marketplace.

An selection of the algorithms that users can try out on Algorithmia

An selection of the algorithms that users can try out on Algorithmia

Learning and understanding aside, it’s also a lot of fun to try things out. For example, the ‘Summarizer’ algorithm which takes in blocks of text, and extracts key topic sentences, turned my post on big data activism into these “key sentences”:

"Facebook controls our Newsfeed- what we see, what we don't, and we have little idea how it works. It turns out that a couple of individuals have already \"hacked the algorithm\" by using certain keywords in their Facebook status, to give visibility to issues they care most about - so maybe it's time for activists to join the game. This great piece by Zeynep Tufekci explains some of the intricacies around how \"the newsfeed rules your clicks\", and there are many more analyses to delve into."

It’s very accurate! There are all sorts of algorithms to look at, and in many cases, you can also look through the source code, and get more of a hands-on approach than normally offered, with the in-browser ‘Algorithmia Console’ allowing you to see the algorithm itself and type in your input directly. In terms of understanding how algorithms run, I’m also keenly waiting for the beta of The Walnut, a service that “gives others the possibility of diving into your algorithms visually”, which should be soft launching in coming weeks.

Being able to see the source code behind the algorithm makes one thing very clear: the algorithm is doing what a human told it to do. As Jenny Davis excellently explains in this article on exclusionary algorithms in Cyborgology:

Algorithms sort in the way that humans tell them to sort. They are necessarily imbued with human values. Hidden behind a veil of objectivity, algorithms have a powerful potential to reinforce existing cultural arrangements and render these arrangements natural, moral and inevitable.

So, then, when we talk about ethics or accountability of algorithms, we actually mean the ethics or algorithms of the people creating the algorithms. What their beliefs are, and the steps they choose to write, determine the process of the algorithm; and as Davis mentions above, we shouldn’t let this “veil of objectivity” hide this, simply because they are carried out by a machine.

But, pragmatically, we have little way of monitoring this before the fact - it seems to me to be somewhat impossible to decree that a certain step in a process should never be included as part of an algorithm. Nicholas Diakopoulos outlines some excellent procedures for algorithmic accountability reporting, including reverse engineering - but obviously, this would happen after the process has taken place and the algorithm has been used, not before.

Though we can’t monitor the steps of the process that humans decide upon to create an algorithm, we can - or should be able to - monitor and have oversight on the data that is provided as input for those algorithms. So maybe, to really understand what effect algorithms are having on society, we should also looking closely at what data is being collected, and who has access to it.