Over the past couple of months, I've had the privilege of travelling to Bangladesh, Canada, Spain and Switzerland, and oddly, I found that all four had an unexpected quality in common; the way in which different languages within the country influenced and affected everyday life and politics.

In bilingual Montreal, anything that was government-run (including a couple of days of the conference that I attended) had to be conducted in both French and English. Wonderfully, this meant government officials would switch languages halfway through speeches and sometimes even halfway through sentences. In between feeling sorry for the interpreters, I thoroughly enjoyed this blend of languages.

It became clear also, that there were many more loan words between their particular versions of English and French, because of the switching; hearing people talk (in English) about the 'animator' of a particular company left me a little confused before realising that 'animateur' in French simply means “organiser” - they were talking about the head of the company, not a designer! Similarly, I'd never heard 'bienvenue' (literally, 'welcome' but in France, always used in the context of 'welcome to... (a place)' rather than 'you're welcome) as a response to 'merci'.

I heard also of resentment growing towards English speakers in increasingly Anglophile areas of Montreal, where staunch Francophiles would respond to anyone in French, even if they understood and spoke English, and knew that the speaker wouldn't understand them.

I experienced a similar phenomenon myself in Spain, when I stopped by Barcelona a week later; in cafes, although I was speaking 'castellano' (ie. Spanish understood in Spain) people would only respond to me in Catalan, despite me having made clear that I didn't understand Catalan.

It was the first time I'd experienced something like this personally. For example, in a cafe I apologised for not speaking Catalan and asked for a bottle of water in Castillian; the waiter went to fetch the water but continued speaking Catalan to me, I apologised again, and instead of simply saying how much I owed in a language I understood, he wrote down the figure on a pad of paper and pushed it towards me. He was very, very determined not to speak anything but Catalan!

When I got to my final destination in Spain, Zaragoza (just next door to Catalunya) I was asked a lot about the upcoming referendum on Scottish independence. People seemed to see lots of comparisons between Catalunya and Scotland, and some were slightly incredulous that the UK had 'allowed' Scotland to hold such a referendum. It was clear that the reluctance of people I met in Barcelona to speak anything but Catalan was part of a much wider battle, one which came up much more frequently in conversation than it had when I was living in Madrid back in 2009.

Politics and language, in this case, were clearly linked, and this was another theme I saw while I was in Switzerland, as, sadly, a vote was passed to impose quotas on immigrants to the country. There were two clear trends in voting for this xenophobic law; firstly, the language split, and secondly the number of immigrants in those areas.

This is a map of the language split in Switzerland; as you can see, the Swiss German population is the largest (63.7% of the population) followed by Swiss French (20.4%), then Italian (6.5%) and Romansh (0.5%).

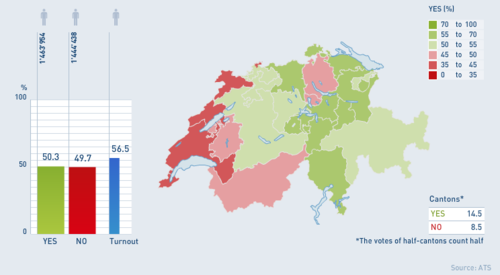

And this is a map of how people voted in the elections; there's a heavy overlap with the Swiss-German areas, and the areas that voted 'Yes', with the exception of Zurich, up in the north.

[image via @electionista]

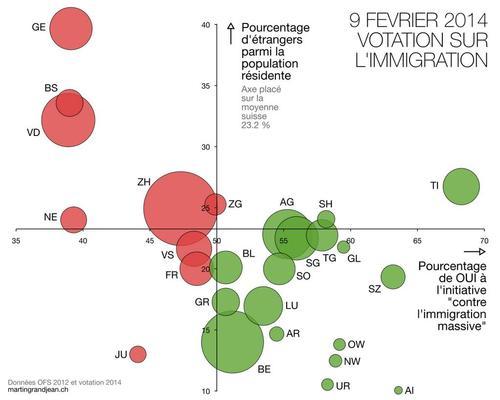

Another trend, illustrated by the chart below, shows that regions with fewer immigrants were more likely to vote 'yes' (ie. for the introduction of quotas) whereas those with high percentages of immigrants already living in the regions tended to vote against the quotas. Fear of the unknown was clearly a motivation for those who hadn't experienced much immigration in their areas, and seemingly didn't want to, either.

[image by Martin Grandjean]

I wasn't aware previously of the extent of the majority which the Swiss German population hold here; clearly, with over 60% of the population, they are the most powerful demographic. I also find it interesting how people tended to vote in blocks depending upon their language affiliation; again, clearly language is a lot more than merely a method of communication.

Another example of the crucial importance of language can be seen in Bangladesh, which is, as far as I know, the first country that was born out of a language-related dispute; essentially, the political movement fighting for the right to use Bengali as an official language in everyday life was a catalyst in the move towards national identity, which were precursors to the Bangladeshi Liberation War.

Having seen so clearly in just those four countries the power and importance of languages within society, seeing statements coming out of the UK encouraging people to study languages for economic reasons, or in David Cameron's words "to seal tomorrow's business deals” frustrates me hugely. I find encouraging language learning by way of promoting trade between countries a terribly sad, and reductive, perspective on the many riches that different languages bring to society.

There are many, many other reasons that us lazy native English speakers should learn other languages; understanding cultures, societies and people being just some of them. If we in native-English speaking countries want to have any chance of understanding the politics, societies and cultures of other, language-diverse countries, we have to stop thinking about language-learning as a luxury or as an economic tool, but instead realise that it's a crucial step towards tolerance and understanding of other cultures.