The Responsible Data in Humanitarian Response meeting held last week in The Hague gave me a lot of food for thought; below, I’ve tried to summarise what my main learnings from the two days were.

Starting on the same page

When we’re coming together in a meeting such as the one held last week, it is important that we all understand some basic key concepts. A few definitions to start, then:

What do we mean by ‘responsible data’?

Here’s a definition that came out of the Responsible Data Forum held in Budapest last year:

Responsible data is the duty to ensure people’s rights to consent, privacy, security and ownership around the information processes of collection, analysis, storage, presentation and reuse of data, while respecting the values of transparency and openness.

And another - “big data”, taken from its Wikipedia page (with my own emphasis):

Big data is a broad term for data sets so large or complex that traditional data processing applications are inadequate.

And just one more - ‘open data’, from the Open Definition:

“Open data and content can be freely used, modified, and shared by anyone for any purpose”

The three terms defined here are becoming quite the buzzwords within the global development sector, and from what I heard last week, we seem to be using them in very different ways. On one hand, this variation could be something to be welcomed - thinking about, for example, what “open data” means to those living in low/no-tech environments. On the other hand, starting from very different understandings of these oft-referred to terms makes it difficult to progress in discussions and debates. It is crucial to begin at the same place, even if we then diverge to make them more specific to our particular contexts.

Responsible data - noun, verb, or adjective?

The aim of the meeting was to think specifically about ‘responsible data challenges’ in the humanitarian sector. I guess I had a bit of a headstart in this field, as this was the third “responsible data” event I’ve attended in the last 12 months, and this, I realised, had given me some assumptions that weren’t present in other people’s minds.

For me, thinking about “responsible data” is a signal of an underlying thread of responsibility running through all aspects of working with data. It’s less of a concrete item (not “here is some responsible data”) and more of an issue to keep in mind throughout (“are we behaving responsibly?”).

To try and make this clearer, during one session, Alix Dunn and I thought through what a “humanitarian data pipeline” would look like. Certain factors that might not be so vital in other sectors come to the fore here, like thinking about communication back to the affected community; finding out what communications channels are most used within the community in question, gaining access to these in a secure and reliable way, and working out what is already known about the community and how reliable and up to date this information might be, for example.

This would likely sit before the first step in the ‘standard’ data pipeline (see right), and could be expanded into a much more comprehensive checklist of ‘data issues to think about’ in the humanitarian sector. In this way, then, thinking about ‘responsibility’ affects all of the steps along this pipeline, and within the humanitarian sector, makes it much more complex.

Humanitarian sector-specific issues

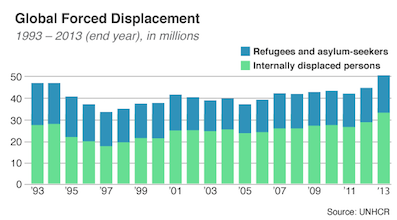

Image source: UNHCR</a>

As was mentioned multiple times last week, for the first time in history there are currently four humanitarian crises designated by the United Nations to be “Level 3” - that is, the most serious classification possible. Last year also brought the tragic milestone that the number of refugees, asylum seekers and internally displaced people worldwide exceeded 50 million people for the first time since World War II.

With this in mind, the issue around time and resource constraints become particularly poignant, which, when coupled with the extremely vulnerable situation of the people reflected in the data, makes this topic even more complex. Many of the processes suggested in this area push hard against these constraints - but the potential risk of ignoring these issues is also huge.

Some of the usual concerns that we think about with responsible data become very difficult to think through, given the sector context: there are limits to, for example, being able to guarantee continued access to data when the people reflected in that data are in the middle of a humanitarian crisis. Notions of consent are turned upside down when a single actor might be asking for someone’s data and simultaneously providing food and shelter - given those power dynamics, who, when finding themselves in such a desperate situation, would refuse consent?

The difficulties of planning ahead on a long term basis were also mentioned multiple times, with the need to be flexible and responsive to changing needs being of utmost importance. In the face of this, the solution of thinking about processes, and putting those processes in place in advance of them actually being needed, was suggested as a way to speed up data-related needs in humanitarian response.

For example, thinking about standardised processes for Public-Private Partnerships, which might enable humanitarian agencies to quickly get access to data held by corporate actors in case of emergencies, like telecommunications agencies holding mobile phone records. Doing this in an ethical and responsible way requires a lot of thought and work, given the levels of bureaucracy on both sides, however - so, working out some kind of standard guidelines that need to be followed before the crisis might make this easier. As was mentioned during the meeting last week though, a lot can be inferred about people through their mobile phone data - where they are, who they call, where they go afterwards - all which, while useful and necessary in a crisis (eg. an earthquake to locate people) can, in other situations, act as detailed surveillance information.

Vulnerabilities, and audience

Another buzzword that was mentioned a lot was that of “innovation”, and among these discussions, I was slightly discomforted by the way in which start-ups and large tech corporations seemed to be held up as a goal to work towards. By nature, the environment in which the humanitarian sector operates is a world away from that of Facebook or other corporate actors, and in my opinion, there are very few truly shared aims between them.

In many sectors, the idea of failing fast and often is seen as progressive and desirable- take, for example, this article from the OECD entitled “Fail Fast, Learn Fast and Innovate”. In this sector, however, “failing fast” can have huge, detrimental consequences on people who are already in the most desperate of situations. Failing fast isn’t an option here, and nor should it be - but instead, we should think about planning ahead for ‘failure’. Having processes to recognise quickly when something isn’t working, and being able to adjust accordingly, is essential. Likewise, thinking through the potential bad consequences of any interventions - take, for example, through doing a dystopian Theory of Change.

Outside of the immediacy of crises, we also thought about project design in the humanitarian sector, and by and large, the suggestion here was to move towards human centred design processes. The “who” became very important here: who are we asking for their opinion, who is having input into the design of these projects? In many situations, the most accessible people in a community aren’t necessarily the ones who are most in need, and gaining access and trust of less visible sections within a community to hear what they have to say is a difficult task.

Conclusions

I was very happy to see that there is a strong desire among those who came together last week to start working through the extremely complex issues mentioned above, and more; though I must admit, I am wary that too many lessons are being drawn from sectors without such precarious working environments without the required adjustments for this sector, and that those buzzwords are being overused without clear understanding and agreement upon what they mean.

I look forward to taking these discussions forward, perhaps through looking at specific case studies and building out required processes from these, or by further developing a humanitarian-specific data pipeline. Get in touch if you’d like to talk more about this!